Negra Murguera is a Three Act Play (versión de Milo J)

¡Bienvenidos, hispanohablantes! Mi español está lejos de ser perfecto, aunque siempre estoy estudiando para mejorar. Intento compartir esta gran canción con el público angloparlante, pero si creen que he cometido errores en mi comprensión del español original o en mis traducciones, agradezco sus correcciones. Si por casualidad alguno de los artistas que participaron en la composición o interpretación de esta canción llega a esta página, por favor, díganme hola y, sobre todo, ¡gracias por la brillantez y belleza de su trabajo!

The moment I came across this song and performance I became obsessed with it, even though my Spanish was not quite good enough to understand it all right away. Musically, it grabbed me by the heart and refused to let me go. The buildup! The rhythm! The sense that there was a story and a dramatic arc that I could not fully understand right away, such a tantalizing mystery! The musical performances all around, and that backing vocal group and its role in the performance. And on top if it all, who is this young singer with such musical presence and a mature, textured delivery? How the hell is he so vocally and musically talented, and refreshingly not at all showy in that cloying Instagram fashion? He is interacting with and listening to the band like a musician, interpreting and relating to the song, instead of mugging to the camera like a TV talent show contestant.

I could not get this song out of my head and I had it playing on repeat.

I knew this much: I had to learn this song and understand it. Here’s what I learned. . .

The Song

Negra Murguera is a rock song originally recorded by the Argentinain rock group Bersuit Vergarabat in 2000, with lyrics and music by keyboard player and poet Juan Subirá and bass player Pepe Céspedes. It was a popular hit that recently was covered by the eighteen year old rising Argentinian rapper, singer, and songwriter, Milo J, accompanied by backing vocals performed and arranged by Agarrate Catalina. Milo J is taking off and gaining international notice and acclaim.

To understand the song, I first had to understand the cultural reference at its heart: la murga. La murga is a musical and theatrical genre, replete with colors and costumes, developed in various countries across latin America, Spain, and Italy. Adapted and reflected through the lenses of different countries, it generally surfaces during popular festivals such as Carnaval, on national holidays, during commemorations of the founding of cities, around sporting events, and during populist or political protests. The word “murga” is used to refer both to a musical style and to the gatherings where it is performed and celebrated. For people in the United States, the closest analogue would be Mardi Gras in New Orleans, which carries its own musical traditions, public celebrations, costumes, and dancing, infused by the mixture of cultural flavors, especially Creole and African influences arising from the poor who live one the margins of society, including indigenous people and descendants of slaves. The musical style of the murga includes a lot of rhythm and percussion, with the power to bring people together in ecstatic celebrations of movement, sound, and color. In Latin America, it is very popular in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Panamá and Uruguay.

Act I: Setting

The story begins with the voice of a narrator, an omniscient third person. The narrator introduces us to our protagonist, a man just waking up, wrecked with hangover, trying to piece together what happened the night before. He recalls a vision of a dark skinned woman, moving as if in a whirlwind. She is covered in dust, that is to say, the grit of life in the barrios away from polite society:

Like a drunk he wakes up, ruined in a deep well

He gets out of bed and begins to remember

The events, dim and hazy, of the night before

A dark skinned woman, covered in dust, in a tumbling whirlwind

He can see her in his mind: she is the embodiment of the murga, a woman of the streets or perhaps the favelas, one of the working people, worn by labor and the toughness of life, with a patched eye and a pure bit of heart. He is thinking of both her and of the mob, of the murga itself, as for him they blend into each other, a place where passion takes over. Next we are carried back to the night before, as if in a flashback, no longer from the narrator’s but instead from our main character’s point of view. The poetic phrase “when passion converts itself into pure grease’” is so evocative but hard to translate literally. It’s more of an image than a description. Grease is rich, it lubricates, it drips from fatty, flavorful foods, the fried foods of the streets. You cook with grease. It’s hot and it sizzles. In the mind of our protagonist, the murga turns passion into pure grease, bringing people together to cut loose and lose themselves in rhythm and motion.

Agarrate Catalina

You are the murga born from the depths of the mob

Of the race that exudes that certain sweat

With one eye patched and a piece of heart

When passion coverts itself into pure grease

Our protagonist is losing himself not only in the rhythms and passion of the murga, but in overwhelming desire. He sees this woman - perhaps she is wearing bright colors or a costume of the murga that blends her identity with that of the murga itself - and her body to him recalls puddles in the streets, her skin toughened by work, maybe calloused. The original Spanish lyric says “piel de vereda,” or “skin of sidewalk/cement.” He is so overcome with longing, so smitten, he wants her to carry him away. He wants to lose (or is it find?) himself in her, with her, and in the murga itself (to the chorus).

Woman of the murga

Ditch water, calloused (literally, cement or sidewalk) skin

Take me with you

He reflects on his surroundings. He’s out of the way in some neighborhood he doesn’t know, outside the city. Its residents are the ones left behind, used and forgotten by those who live comfortably. They are poor. Who knows what goes on in those neighborhoods? They are alien to him. The area may be considered dangerous by people who work in offices downtown, who live in greater comfort. Turning from the mysteries of this place, he thinks also about himself, what he brings with him: sadness. But his sadness, ordinarily held in place as water in a glass, is overflowing Tonight the glass has broken and his sadness spills out,. With the beating of the murga drums, he is dodging and weaving around his sadness like a soccer player dribbling the ball across a field, desperately dodging to stay in control. The beating music helps him do that. We have our first indication here that our protagonist is a musician at the murga, a drummer.

To a worldly neighborhood outside the city that has no status or power

Where they do good things or bad, how would I know?

Sadness fills a glass that shattered and spilled all over

That day when I weaved and dodged around it to the beating of my drum (the literal image is of a soccer player dribbling and weaving through the field)

Once again, dodging his sadness, he urgently desires to be taken away by this dancing woman, whose long hair flies all about as she gyrates and dances (back to the chorus, expanded).

Woman of the murga

Ditch water, calloused (literally, cement or sidewalk) skin

Take me with you

Woman of the murga

Under your starry sky, with hair flying all around (the image is of long hair flying around wildly as people gyrate and dance)

Take me with you

He’s drawn further and further into the ecstasy of the music, the crowd, the beat, the dance. He’s playing his drum, both creating this energy and feeding off of it, becoming one with it. But he is still somehow partly outside of it all, an observer, captivated by this woman. He vows that he’s going to play that drum with such force and passion that his hands will bleed. And like a greek chorus in the background, we hear the song of the murga in the form of the lalala harmonies wrapping around his inner monologue. (This section is like a second, different chorus.)

I'm going to play until my hands bleed (lalala, lala, lala)

I'm going to play until my hands bleed (lalala, lala, lala)

I'm going to play until my hands bleed (lalala, lala, lala)

I'm going to play until-

Act II: Action

Scene change: we now briefly return from the flashback of the night before to the morning after, to the voice of the narrator. Our musician friend is struggling to recall the music, trying to recapture and sing the song of the murga. But the tune escapes him, and as a result he becomes pensive.

In the midst of his hangover

The musician tries very slowly to sing

But it's a vague, empty lament

Like the passing wind, which makes him think. . .

And now for the first time we hear directly from the murga, in its full voice and harmony. It has been with us in the background of the story and in the music in the voices of the choral group Agarrate Catalina. Now we hear them directly.

La murga

Lalala, lalalalalala

Lalala, lalalalalalalalalala

Lalala, lalalalalalalalala

Lalala, lalalalalalalalala

Lalala, lalalalalalalalala

The scene once again changes, and we flash back to the night before. We have returned to our main character, the drummer. The dancing woman has become his musical muse as he beats his drum. His swears an oath to her to play his drum and not leave it, giving her his music to fuel her dance and abandon. In all the mob, he sees only her. She is now his purpose.

You are the muse that brings me inspiration!

I swear I won't leave my drum

Because seeing you, dark haired woman, is such a beautiful feeling

I only play so you can dance

Well, maybe that oath didn’t last long? Immediately after swearing he would not leave his drum, he maybe does just that, or perhaps he takes a portable drum with him. The poetic lyrics are unclear and leave the details open to the listener’s imagination. He recalls that he joined the mob and is moving her hips. Did he actually leave his drum and start to dance with her? Did he take a drum with him, maybe strapped around his body, and join the dancing mob? Or is his joining the crowd a spiritual or emotional act, an internal surrender? Is he moving her hips physically as a dance partner would or is he doing it with the rhythm of his drum? The text is unclear, open to the listener’s interpretation. In this version of the chorus, he is referring to her now explicitly in terms of her color (“negra murguera” versus “murga murguera”).

Black murguera

I got into the group and moved your hips

Take me with you!

Cut! We arrive at another scene change, switching time and place again. We are still with our protagonist, but now from the point of view it seems from some time after that night, looking back. He’s reflecting on what people said about how he behaved with this woman in that crowd that night. Right away, it seems, they began gossiping. In the next lines he is more or less explaining or defending himself. He had let himself go and in response to people’s comments and by way of explanation he responds, “So what do you want from me? What can I say? I was overcome by tenderness and passion.” And then in a way here the song breaks what in a theater would be the fourth wall, because he refers now to this very song we are listening to, speaking directly to the listener and to his critics. He says to us and to the woman that these melodic verses came out of him as if they were ripped out or stolen out of him by her, his muse. He says the song is an irrefutable proof of his love for her.

On the street, they're already saying that I wasn't myself

So what can I say? If tenderness poured out of me!

And these sweet verses that your dance ripped out of me

Are an irrefutable proof of love

We transition back to that night as the song rejoins our protagonist dancing with this beautiful muse. He wants desperately for her to take him away. In the light of the blue moon, the very sight of her skirt - the chosen word, pollera, suggests a brightly colored skirt of a murga costume - smashes his sadness or breaks apart his pain, that sadness that before overflowed and that he’s been dodging through the night with the help of the crowd and the music. Amid the ecstasy of the moment, he feels tempted to “put his foot in it,” conveyed by a Spanish expression that connotes making a social faux pas or doing something socially awkward, even to the point of blundering or making a fool of oneself. It suggests what in English might be described as “going overboard,” or “messing up.” The sort of impulsive thing one may do while drunk. Is he thinking of confessing his love? Of asking her to run away with him, leaving his life behind? Does he have something else in mind? We don’t know. All is left to the listener’s imagination, and he is not telling us, or he does not remember.

Black murguera

I got into the group and moved your hips

Take me with you!

Black murguera

Under the blue moon, the light shone on your skirt

A sight that breaks all my pain

And I feel like making a fool of myself (literally: putting my foot in it), lalala, lala, lala

And I feel like making a fool of myself (literally: putting my foot in it), lalala, lala, lala

And I feel like making a fool of myself (literally: putting my foot in it), lalala, lala, lala

And I feel like- (black murguera, lalala, lala, lala)

And I feel like- (black murguera, lalala, lala, lala)

And I feel like- (black murguera, lalala, lala, lala)

And I feel like- (black murguera, lalala, lala, lala)

And I feel like-

Act III: Aftermath

Songwriter, poet, lyricist and musician Juan Subirá

This climactic reverie is now interrupted by a return to the voice of the narrator. Our protagonist is walking home, drunk, alone, taking his steps carefully as he (probably) wobbles. The first two lines below are sung by the chorus, functioning like a greek chorus, telling the story from the narrator’s point of view. The next two lines come softly from the mouth of the protagonist himself, as if reflecting that next morning or perhaps even later. He is rueful, even remorseful. Of his loss of memory of that night, he blames it on being drunk, or on himself for being a drunk. And so the song, the saga, ends. He is left with his regret, his sadness, the cloudy outlines of an exhilarating memory, and a song.

And as he walks back home

Walking intentionally, stepping carefully along the path he must take

He blames it all on being drunk

For having forgotten the black woman

In a bar

Analysis

Let’s take a quick look at this story as if it were a play, a piece of literature. What’s in it?

Love, Connection, and Escape

Our musician protagonist is lonely. We don’t know a lot about him other than that he’s a musician and he carries a deep sadness with him. So, he’s like most (presumably young) men, then. This is all very human. He aches for love, longs for connection, and he wants to run away. From what? His sadness. Or is it from himself? The murga, with its costumes, drums, the rhythm of the mob, the music, all these things combine to take any us out of our thinking, worrying heads, out of our daily lives, into a world of pure feeling and movement, living through our bodies, instead of our minds, immersing ourselves in color, smells, sweat, bodies, the ripe aroma of the possibility of sex in the air, a dense tumble of humanity and electricity. He desperately wants this woman to take him away with her, to jailbreak him from his prison of sadness, his pain. It’s an alcoholic dream, a flight from reality, but in those fleeting moments, gazing at her, moving her hips (either with his drum beats or dancing with her directly), he feels alive, whole, free. In the end, he lives with the regret not only of not winning her, but of struggling to remember her, of forgetting her, save that which he transferred into his song. Hooray for art! If comedy is tragedy plus time, then art is maybe suffering plus craft. All of this is quintessentially human, and beautifully rendered in the song: loneliness, desire, love, loss, regret, shame, ecstasy, joy.

Class and Race

We don’t know where our main character, the musician, comes from, or what kind of family he grew up in, but whatever it was, he is not from the lowly parts of town where the murga takes place. What goes on in this part of town? Who are these dusty, calloused people, with passion, heart, and eyepatches? He does not know. He is not one of them.

Race and color are major parts of this story. The murga’s costumes are colorful. Blackness is right there in the opening verse, and then it rises to prominence in the return of the chorus at the story’s climax: negra murguera. The murga itself is a creation of people of color, replete with African and indigenous influences, costumes, and rhythms. In the story, the woman is the embodiment of the murga and she is, we are reminded repeatedly, black. Our musician protagonist presumably is not darkly complected, or why else would her blackness be such a significant point of intrigue for him, especially as the story approaches its climax?

There are two ways to interpret these dynamics of class and race inside the story. Both can be right, and they can exist simultaneously. I’m not judging here, but rather mining the depths and complexity of the song.

On one hand, the song can be taken as a celebration of the freedom and creativity of the murga culture, its creators, their communities, and how they sustain and preserve celebration and the beauty of life in ways that more uptight, socially climbing parts of society not only leave behind but frankly often sneeringly repress. The main character longs for that freedom, perhaps especially as a musician and artist, but that longing is of course not unique to artists. It is human. Everyone needs and seeks connection and community, self-expression, release, and love, but modern life in cities and under capitalism instead pits us against each other, against ourselves, against the planet and against nature itself.

That alienation inherent in communities of privilege and power under capitalism is simultaneously also bound up in the history and cultural backdrop of exploitation and colonialism, which of course is inextricably tied to race and the history of slavery. Literature is full of examples of light skinned people using people of color as sidekicks and catalysts for their own main character self-discoveries. In such stories, people of color are catalysts, objects. They are sidekicks, shamans, mammies, sage elders engaged with in passing. They are not subjects. These stories include them more as archetypes than as three dimensional humans with lives, dreams, struggles and motives of their own. These white protagonist stories where darker skinned people appear are not stories of people of color.

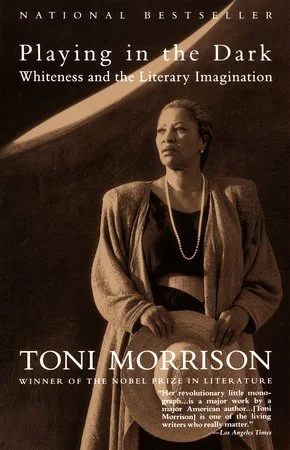

To underline that absence in this story, who was this woman? What did she want when she came to the murga? If the drummer went to dance with her, did she want that? What is her part in the story? Where is her voice? We hear the voice of the narrator, that of the murga, and that of the protagonist. But In this song, hers is silent. How might our musician friend have ”put his foot in it” with her at the climax, and how did she respond? Our drummer does not report that or he does not remember, although we know on the streets people are gossiping about his actions that night, saying he was not himself. What did he do? He seems to feel the need in the song to defend himself, but for having done what, actually? Do we have the whole story? We are faced with gaps. Probably no one has deconstructed these themes of the use and representation of blackness in the stories of light skinned people in literature more effectively than Toni Morrison in her seminal book of criticism, Playing in the Dark.

With perhaps an unconscious dynamic of cultural tourism or hidden colonialism, combining elements of both class and race underlying the story, the song conveys not only truths of the human experience related to longing, art, loneliness, love, and desire, but it also places all of this as it occurs between two specific people within a broader, sweeping social context that is eminently real: a world of economic winners and losers, a world of the powerful and the powerless, of the privileged and the exploited, of the light skinned and of those relegated to the social caste of blackness. All of this makes the song a much more complex and nuanced work of art than what at first meets the eye ear.

Music

The song is a banger. It just is. The performance in the video above is terrific. Here’s another version live on stage before a stadium audience, with the members of Agarrate Catalina donning murga costumes.

The song has a unique storytelling structure with tempo changes and modal variations throughout. I won’t go overboard into musical structure but briefly, the song is probably best understood as written and performed in the D harmonic minor scale, a scale that tends to evoke epic sadness or tragedy. But the fit in the scale is a little loose because the song contains many chords adjacent to or modally outside of that scale. It fits just as well into the A Phrygian dominant scale, and the choice to locate it in D harmonic minor is most correct because the opening riff starts in D minor and the closing at the end resolves in E minor after the song changes key to move a full step up from D minor just before the story reaches its climax. This happens right after we hear directly from the murga in the form of its lalalala celebration of song, when we arrive at this line: “Sos la musa minusa que me da inspiración!”/”You are the muse that brings me inspiration!” After this point the rest of the song repeats patterns we have already heard, but a full step higher after the key change.

A look at the other scales close to D harmonic minor is a little illuminating. The A Phrygian dominant scale is most associated with world music, gypsy songs, flamenco, or even Jewish music. There are three more closely aligned scales to consider: G Ukrainian dorian (known also for gypsy and Eastern European music), B flat Lydian #2 (considered generally to be yearning, emotional, serious), and D flat Super-Locrian diminished (associated with complex latin music). Musically, this song conveys elements of all of these moods.

Considered from the framework of the D harmonic minor scale, the introduction right away includes a borrowed chord that does not belong in the scale: immediately after the D minor to start the introductory riff, we arrive at an E7, followed by G minor and A7. The later two chords belong neatly in the scale. The E7 is borrowed, a modal deviation from outside the D harmonic minor scale, whose second degree chord would normally be an E diminished, not the major E7.

The song frequently makes use of these modal, borrowed first and second degree seventh chords to transition between sections or even within sections. It occurs before the first two instances of the chorus (from F7 to G minor) and then again later before the last chorus (but after the key change to E minor) before the last chorus (from G7 to A minor). Within the verses (after the narrator’s introductory section), a similar change is embedded in the first line going from the D minor to D7 at the very end of the phrase (Verse 1: “Sos la murga que nace en la entraña del malón”/”You are the murga born from the depths of the mob”). It functions as a leading tone. The D minor to the borrowed E7 also occurs during the chorus at the end of the second line (“Agua de zanja, piel de vereda”/Ditch water, calloused (literally, cement or sidewalk) skin”). In all of these cases, the introduction of the borrowed seventh chord creates a leading tone with unexpected color and dissonance that is quickly resolved by ending the next line in each case on the fifth chord of the D harmonic minor scale, the A (either the major or major seventh voicing). Sevenths are used like this a lot in jazz, too.

Conclusion

Okay, I admit that was a lot. The blog post grew as I drafted it.

I guess the bottom line is I’m making a case here that this song can be enjoyed on multiple levels. You want to take the ride just for the vibe of the music and the performances? Great! That’s what hooked me in and that’s all you need.

Want to decipher the story and follow along with the structure, and see how it works as a kind of musical stage play? Great, you can do that too. It has the depth and it works. In Spanish, the lyrics are more poetic than can be rendered here in my translation, but even in English, you can get access to the song on this level as I’ve described above.

Do you want to review and consider the story as a work of literary art and explore what it reflects about the human condition? The song holds up on that level too, as I hope I’ve convinced you by now.

Anyway, this was fun to do. I’ve converted my obsession with this one song into an essay. I play it on my guitar. If you’ve enjoyed this article, please let me know why below with a comment, or even tell me where you disagree. If you think I’m full of shit and that I’m overcomplicating things, that’s fine, too. No matter what, thanks for reading this far!